November 12, 2019

•

7 min read

In our previous posts, we took a look at what happens when we eat meals and also discovered how our bodies break down and use fat in found in our food. Now it’s time to turn to carbohydrates (a.k.a. carbs).

When you eat, the carbohydrates in your food are broken down into individual sugar molecules (mainly glucose) that end up in your bloodstream.

In response, your body produces a hormone called insulin, which encourage your cells to take up sugar from the blood and either use it or store it for later.

We can observe how well your body responds to carbohydrates by measuring the levels of glucose in your blood after you eat.

When we eat and blood glucose levels begin to rise, our bodies should be able to deal with it in a swift and controlled manner. As a result, blood sugar levels should never become too high or too low.

A rapid spike in blood sugar after eating a lot of sugary foods is often followed by a crash as our metabolism rushes to deal with the sudden arrival of all those carbs.

Crashing blood sugar makes us feel tired and hungry, which can lead to overeating and increase the chances of weight gain.

If your blood sugar levels remain high for too long, it becomes harder for the normal insulin response to work properly.

Your cells gradually become resistant to insulin, meaning that even more of it is made to try and compensate. High levels of sugar in the blood can also directly damage insulin-producing cells in the pancreas.

Long-term insulin resistance and poor blood sugar control can eventually lead to type 2 diabetes.

But the story doesn’t end there. Poorly controlled blood sugar levels cause blood vessels to harden and narrow, increasing the risk of having a heart attack or stroke. Blood vessel damage caused by diabetes can also lead to blindness, painful skin ulcers, loss of lower limbs and kidney problems.

Many research studies use oral glucose tolerance tests to see how well people can control their blood sugar levels after eating carbohydrates – something we’ll look at in more detail in our final post of this series.

The test involves giving a fasting blood sample before eating or drinking a precise amount of carbohydrate, and then giving another blood sample after a set period of time.

Unfortunately, one-off tolerance tests only provide a snapshot of what is going on in your body. A single blood test after a defined time may capture the peak blood glucose level in one person but miss it in another.

To make things more complicated, our PREDICT studies show that even identical twins can have very different nutritional responses.

For example, here are two very different blood sugar responses from two identical twins in our PREDICT 1 study, who ate exactly the same meal containing 85 grams of carbohydrates at exactly the same time in the morning. Time (minutes since eating) is running along the bottom of the graphs, blood sugar levels are up the side.

Single-point tests also don’t tell us much about your responses to combinations of food in meals eaten throughout the day, or how stable things are over a longer period of time.

As a solution, nutrition researchers have started using HbA1c tests to determine how well people can control their blood sugar levels. HbA1c is a compound formed when proteins in your red blood cells bind with sugar in your blood.

Measuring HbA1c gives a good indication of what your average blood glucose levels have been over the past few weeks, but it still doesn’t capture day-to-day data.

The only way to truly know how your body responds to carbohydrates is to continuously measure the levels of glucose in your blood. That’s why our PREDICT studies use continuous glucose monitors – clever gadgets that measure the glucose levels in the fluid under your skin.

During PREDICT 2, participants wore a continuous glucose monitor at home for 11 days which records their sugar levels every 5 minutes. This gave us a detailed overview of how their blood sugar changes after every meal or snack, and revealed exactly what happened in response to exercise or overnight as they slept.

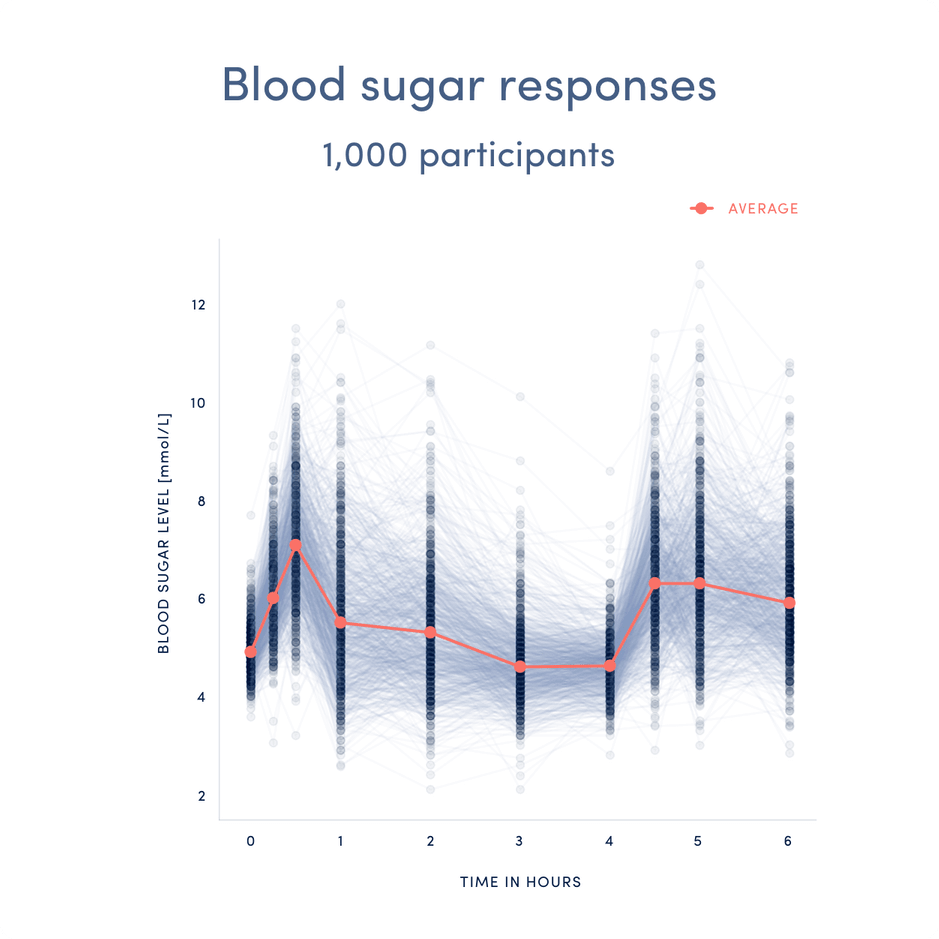

Responses to carbohydrate vary wildly from person to person. Our PREDICT-1 study showed huge variability in blood glucose responses between people eating the same foods, even among identical twins.

Blood sugar responses to identical meals measured in 1000 participants in the PREDICT 1 study.

Although many factors have been linked to changes in carbohydrate responses, including some things you can’t change like your genes, ethnicity, and age, the good news is that it’s possible to improve or compensate for poor responses to carbs.

It may sound obvious, but the best way to improve your blood sugar control is by eating foods that have the smallest impact on your blood glucose levels. Just thinking carefully about what you eat at your next meal and what you do for the rest of your day can improve your blood sugar response:

Unfortunately, you can’t make changes to your lifestyle today and expect your blood sugar control to be hugely improved tomorrow. That’s because various aspects of your long-term lifestyle also impact your carbohydrate responses:

Our PREDICT studies are the largest of their kind in the world, investigating how many factors combine together to affect our responses to food, including our responses to carbohydrates.

We’re combining continuous glucose monitoring with other large-scale data and machine learning to predict personal nutritional responses to any meal so you can better understand your biology and eat the best foods for you! Now you can use our at-home test kit to get the whole picture on you and be empowered to eat for your body, for life.