August 29, 2020

•

We are all bombarded with advice about what we should and shouldn't eat, and new scientific discoveries are announced every day. Yet the more we are told about nutrition, the less we seem to understand.

In his newest book, Spoon-Fed, Prof. Tim Spector (scientific co-founder of ZOE and professor of genetic epidemiology at King's College London) reveals why almost everything we've been told about food is wrong and encourages us to rethink our whole relationship with food.

For years we’ve been told that eating fewer calories and exercising more is the answer to weight loss. But is eating well really as simple as asking yourself “How many calories should I eat to lose weight?”

Find out in this exclusive excerpt from Spoon-Fed.

Calories in, calories out – this simple rubric defines the weight-loss strategy for hundreds of millions of people across the world. The diet industry is based upon this simple idea, but contemporary research is beginning to show that what we see as fundamental to a healthy lifestyle could be wrong – and even dangerous.

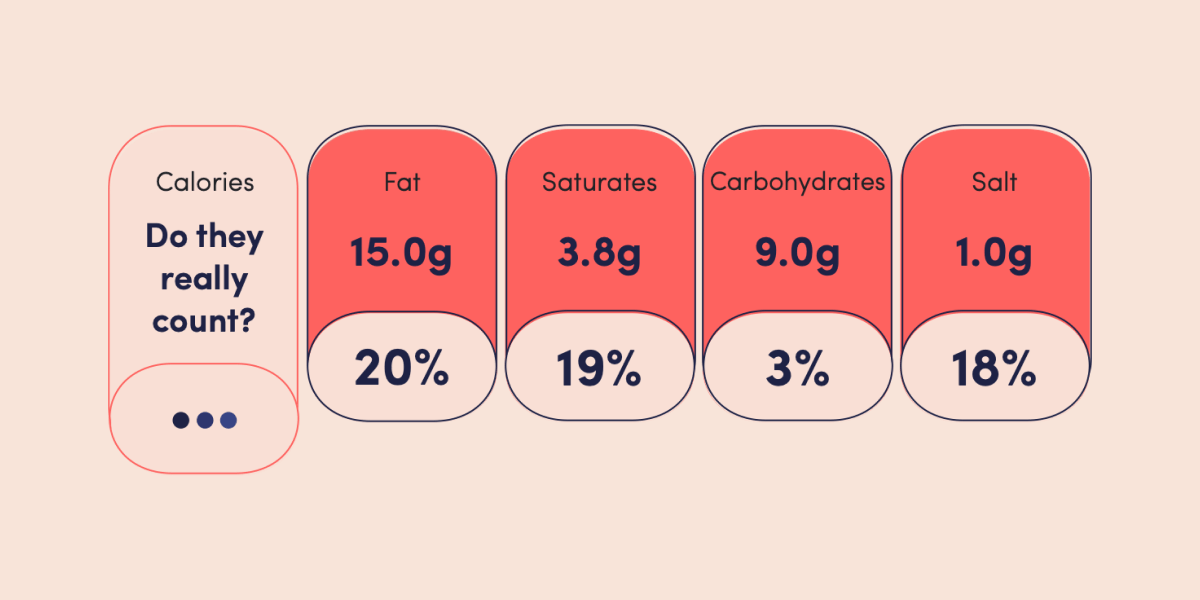

While the central idea behind calorie-restricted diets is fairly self-evident – energy entering any living being equals the energy it puts out – most of us haven’t a clue what a calorie actually is, despite it being displayed on every food label.

Doctors like me were once taught about calories and kilojoules at medical school, but have long since forgotten any details. The general misconception is that they are a direct and precise measurement of how fattening a food is.

Antoine Lavoisier, a famous scientist living at the time of the French Revolution, was the first to understand that we ‘burn’ food as our source of energy. He measured the calorific units in food by inventing a bomb calorimeter, which was like a mini oven surrounded by water. This allowed food items to be burnt in order to measure their calorific value based on the heat that they each gave off to the surrounding water. He also fed unfortunate guinea pigs different diets and invented a similar device to put them in while alive, surrounded by ice, to observe the effects of how they converted food into heat energy.

In the late nineteenth century, an American scientist named Wilbur Atwater dedicated his entire life to conducting experiments to determine the calorie count of over 4,000 food items. He not only measured the energy given off by the food, but would also feed them to volunteers and collect all the resulting heat, urine and stool samples produced. He would then carefully burn the urine and stool samples and work out how much energy they contained.

He worked out that fat was roughly twice as energy dense as carbohydrates or protein, which was the beginning of the idea, now so intrinsic to our ideas about health and nutrition, that fat is particularly ‘fattening’. His findings are still used today on food labels around the world and his work had a profound and lasting effect on the power and precision of the calorie as a unit to measure energy.

At first glance, this all seems to make perfect sense: we work out the calorific value of our food, then how many calories we need to eat to lose weight, and hey presto – we have a diet.

It seems like an easy and straightforward formula for weight loss, and it’s easy to understand why the calorie has become a buzzword in the health industry. But although we can accurately measure the calorific value of a meal, the relationship between those calories and our body is much less straightforward.

The biggest problem with the calorie is not the measurement itself – which does serve some crude purpose in allowing us to distinguish the relative energy gained from eating celery vs eating potatoes – but in giving us a false sense of security and precision. The use of the calorie has been great news for the food industry, sending sales of ‘low-calorie’ foods and snacks sky-rocketing and keeping marketing departments busy, while health regulators have been able to show their governments quantifiably that they are doing something positive. But the calorie has been a disaster for the average consumer.

We have been fooled into thinking that food is something that can be spoon-fed in precise quantities, and conned into eating low-calorie diet foods that fail to satisfy our hunger and made by diluting real food with nutritionally empty chemicals.