January 15, 2021

•

The latest results from our PREDICT study - the largest study of human nutrition and health of its kind in the world - shed light on the complex interactions between our gut microbes (microbiome) and health, revealing how specific species of gut microbes are linked to indicators of good and poor health.

For the first time, we’ve been able to identify 15 “good” gut microbes that are linked to indicators of good health, and we’ve also found 15 “bad” bugs that are strongly linked to markers of worse health.

Let’s take a closer look at the “good” and “bad” bugs living in our guts.

We’ve known for a while that a diverse microbiome with many different species of microbes is more healthy. Hosting a wide variety of bugs in our gut means that they can share jobs between them and recover more quickly if something happens, such as taking antibiotics.

But there is more to a healthy gut than a wide range of microbes, according to our scientific expert Professor Nicola Segata from the University of Trento.

“Many different bacteria living together in our gut usually means a healthy microbiome - this has been known for some time,” he says. “But now we can go beyond just the basic diversity to look at the links between individual microbes and health.”

In our research we analyzed huge amounts of data about diet, health, and the microbiome from more than 1,000 participants, using cutting-edge metagenomic sequencing techniques and sophisticated computer algorithms to piece it all together.

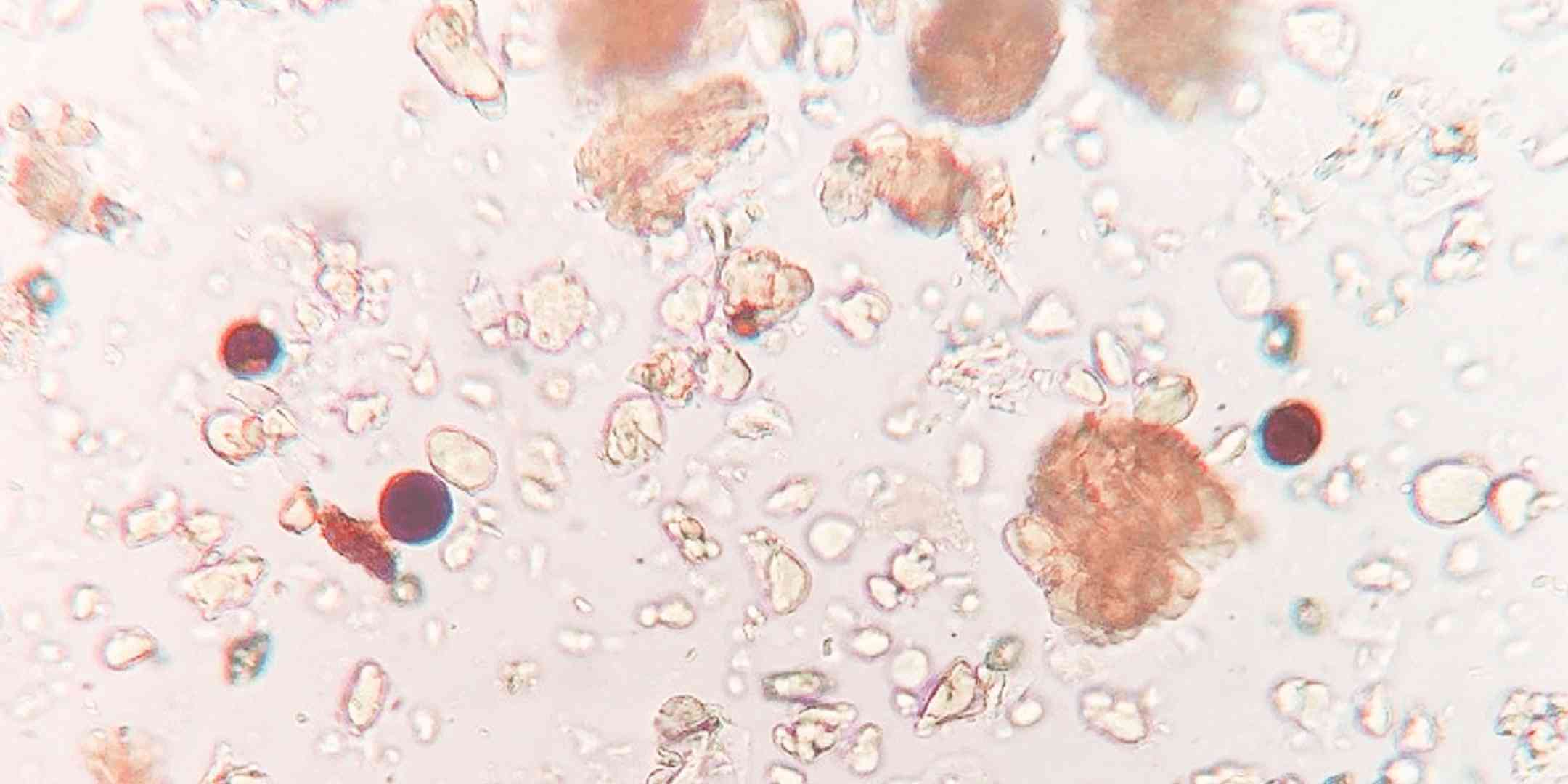

“Metagenomics is a relatively novel technique that allows us to look inside the microbiome,” Nicola explains.

“You take one gram of poop and using high-throughput sequencing machines - the same machines that can read the human genome - we read the DNA of the whole microbial community. But in a metagenomic sample, there are genomes from multiple microbes together, so it is like trying to solve many puzzles together, which is very difficult.”

After sifting through all the data, we found 15 microbes that were associated with a healthier heart and metabolic profile (which we informally call “good” microbes).

We also found 15 microbes that were associated with markers of a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, as well as having higher inflammation and more belly (visceral) fat (which we refer to as “bad” microbes).

Importantly, we were also able to identify nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns that were associated with these “good” and “bad” microbes.

Humans are complex, and our diets and microbiomes are complex too, making it challenging to disentangle links between specific microbes and particular foods.

The size and depth of the PREDICT study allow us to pick up associations between individual species of microbes and aspects of diet and health.

Flavonifractor plautii, for example, seems to be a real “baddie” that is associated with less healthy foods and markers of poor health, including excess belly fat.

On the other hand, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which is linked to healthier foods, is generally carried by those with better markers of health.

Some other “good” bugs are Prevotella copri and Blastocystis, which are both associated with having healthier, more controlled blood sugar levels after eating.

This is important because unhealthy blood sugar spikes and crashes can leave you feeling tired and hungry after meals. Repeated, unhealthy blood sugar and blood fat responses over time can contribute to poor cardiometabolic health in the longer term.

Interestingly, we still know little about some of these microbes, despite their strong links to health. For example, Firmicutes bacterium CAG95, which is associated with a healthy diet and better markers of health, is poorly characterized and has never been grown in a lab before.

The good news is that whatever the mix of microbes we have in our gut, there’s growing evidence that we can manipulate our microbiome by changing what we eat. In turn, this offers exciting opportunities to improve our health.

“What we are showing here is that it is complex: we can’t blame one microbe for poor health, or pin good health on another,” says Tim. “But at the same time, what we’re finding is that these important microbes are also linked to diet, so if we change what we eat we can change our microbes, which would then shift our health.”

Because we each have our own unique microbiome, there won’t be a one-size-fits-all approach to nutrition.

So, do you have the “good” bugs? And what should you eat to help them thrive?

With ZOE, you can discover which of these microbes are living in your gut and get insights into how your body responds to food. After taking our at-home test, you’ll get a detailed gut health report including a Microbiome Health Score™ and the prevalence of the 15 “good” and 15 “bad” microbes, along with a list of personalized gut boosters that may support your gut health.