February 15, 2021

•

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought dramatic adjustments to daily life and work, creating stress, anxiety, and uncertainty. Many people have had their eating and activity patterns disrupted, especially in places where stores, restaurants, and gyms have been closed.

We hear stories that these changes have contributed to unhealthy diets, reduced physical activity, and weight gain (the so-called ‘Quarantine 15’), but there’s little hard scientific evidence so far to back this up.

To build a clearer picture of how the pandemic has affected health behaviors, the ZOE COVID Symptom Study app asked people how their diet, exercise, and sleep habits had changed during the pandemic. More than 1 million people took part, making this the largest study of its kind anywhere in the world.

The findings, which are currently under review for publication in a scientific journal, show that contrary to popular opinion, the pandemic has led to positive rather than negative changes in eating and exercise patterns for some people. For example:

In our latest expert webinar, Dr. Sarah Berry, Nutritional Scientist at King’s College London and our lead nutritional scientist who designed the survey, Professor Christopher Gardner, a Nutritional Scientist from Stanford Medical School, and Rebecca Tobi, a Registered Associate Nutritionist from The Food Foundation in the UK, discussed the top-line findings from the study and how life in lockdown had shaped our diet and health habits.

The ZOE COVID Symptom Study is the largest study of its kind in the world, with more than 4 million contributors using the app in the UK, US, and Sweden.

We asked app contributors to fill in a detailed survey looking at how their diet and health behaviors changed during COVID-19 compared with February 2020, before the pandemic struck.

We then used this data to create a ‘disruption index’, representing how much each person’s life had altered in five areas: diet quality, snacking, sleep, exercise, and alcohol consumption.

Everyone who participated in the study was allocated a disruption index on a scale of zero to five, with five being the most disrupted and zero being the least disrupted.

Our data showed that two-thirds of participants experienced some level of disruption to their diet and lifestyle, however, the effects of the disruption varied widely between individuals.

Although most people in the study reported changes to their diet and health behaviors from before the pandemic, these were not all negative. Contrary to popular opinion, the researchers found that the pandemic had acted as a catalyst for positive health changes for many.

The pandemic may have actually provided the opportunity for many people to make changes to improve their diet and adopt a healthier lifestyle.

The greatest improvement in diet quality and physical activity was seen in those individuals who had a less healthy diet and behaviors to start with. Those who came into the pandemic with a healthier diet and lifestyle tended to retain these positive behaviors.

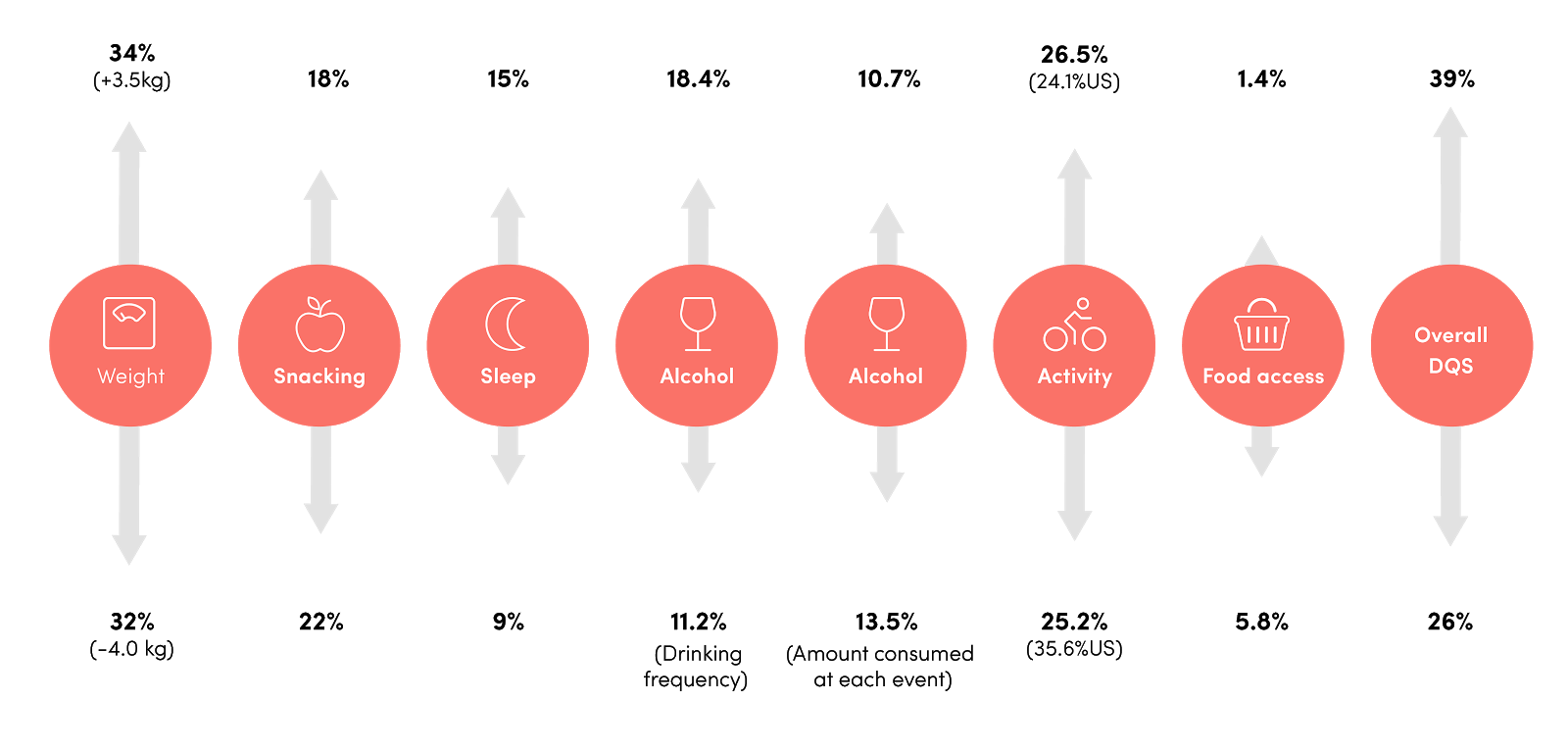

This figure shows the proportion of people who experienced increases or decreases in weight, snacking, sleep duration, alcohol frequency, alcohol amount, physical activity, food access, and overall diet quality (DQS) during lockdown compared with before the pandemic.

These changes were similar between the US and UK, except for physical activity. A slightly smaller proportion of people in the US increased their activity levels during the pandemic compared with the UK, while a larger proportion of US respondents did less (around 35% in the US compared with 25% in the UK).

We are all individuals with our unique circumstances, and we all respond to change differently, so it makes sense that our data showed massive variation in how people’s lives changed during the pandemic.

For example, 22% of participants reported snacking less during the lockdown, while 18% said they snacked more. Similarly, some people drank more alcohol, while others drank less.

Although weight didn’t change on average, we saw that the weight change was highly variable between people.

The results showed that 32% of participants lost an average of just under 9 lbs, while 34% of participants gained an average of 7.7 lbs, with people who experienced more disruption gaining or losing more weight than people whose lives were less disrupted.

It’s worth noting that weight loss or weight gain alone is not always a reliable indicator of good or bad health. Someone could lose weight yet have unhealthy blood fat or blood sugar responses and other risks such as diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic health problems.

Ultimately, our findings confirmed that looking at the population average is not the best indicator for how individuals within a population are doing. It’s the individual results that reveal the most information.

Looking at the variability of responses between individuals highlights how some groups have been more affected by the pandemic than others.

Through this research, we found that the highest disruption was seen in younger females and those living in more deprived areas.

While our research didn’t specifically investigate why this might be the case, several papers have been published suggesting possible reasons for diet and lifestyle changes during the pandemic:

Before the pandemic, we all had our routines. What’s clear is that the pandemic has disrupted that for many people. Now the question is about building new systems around what your life is like right now and what it will be, despite whatever is thrown your way.

Be kind to yourself and don't try to fix everything all at once. Think about the areas where you feel like you have the most room to improve in, and what you feel motivated to work on first.

Establishing new routines and focusing on developing new healthy habits should be sustainable. Instead of turning to extreme measures like fad diets, which just don’t work for most people, why not make this the year that you stop fighting against your biology?

The ZOE COVID Symptom Study will be releasing a new survey in app soon to find whether any of these healthier - or unhealthier - habits have stuck in the second half of the pandemic.

If you aren’t involved in the ZOE COVID Symptom Study yet, please download the ZOE COVID Symptom Study app (available in the UK, US, and Sweden) and take a few minutes to let scientists know how the pandemic is shaping your life.